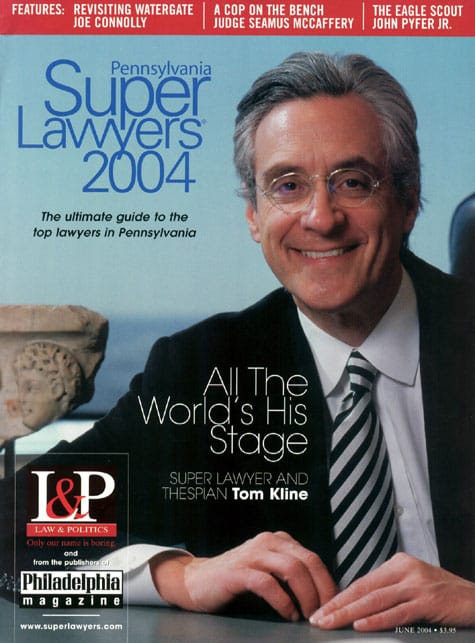

Tom Kline was selected as the No. 1 lawyer in Pennsylvania for four consecutive years -- 2004, 2005, 2006 and 2007 -- by Pennsylvania SuperLawyers, "the ultimate guide to the top lawyers in Pennsylvania." Kline was the top point getter among more than 39,000 attorneys in the commonwealth. The following is the cover article from Pennsylvania Super Lawyers 2004. Click here to read the latest from Super Lawyers.

Tom Kline, the Marlon Brando of the courtroom, follows a method of his own when he's in front of a jury. He dons his costume, one of his trademark black, stylish suits and, like any top performer, he never misjudges his audience.

"You can't underestimate the intelligence of the juror," Kline says. "But at the same time, you have to present the material in a fashion that can be readily absorbed and grasped."

The Kline Show is so good that one judge who saw him in front of a jury felt compelled to write an article called "Trial as Theater." Kline was flattered, but, more importantly, the article gave him an idea. He took the title and turned it into a continuing legal education program - a one-man show at the Wilma Theater in Philadelphia. He bases the production on actual cases he's tried and, as far as he knows, he's the first to use the stage for CLE.

Anyone stepping into Kline's office can see that theater is a big part of his life. A series of ancient Roman mosaics depicting theater masks, just some of the antiquities he collects, adorn the walls. Mixing drama and education was natural for the 56-year-old, whose first was a junior high social studies teacher.

Kline was born in Hazelton, a coal-mining town in northeastern Pennsylvania, where his father managed a dress factory. His first job was filling coal bins around the neighborhood. Kline attributes his small town childhood with giving him a down-to-earth perspective on his practice in personal injury law.

"I knew early on growing up that people were unfairly injured under many circumstances," Kline says. "I understand the hurt that can be caused to another person and it has motivated me to see that it doesn't happen unnecessarily. When an injustice has been done, its an impulse I have that there should be some measure of redress. And maybe that sounds like a platitude, but I really believe it."

When he finished high school in 1965, Kline attended Albright College, where he majored in political science. Although he eventually planned to study law, Kline returned to the area in which he grew up in 1969 and taught social studies to disadvantaged sixth-graders. There he did some social studies of his own: he met his wife, a fifth-grade teacher named Paula. The couple of 31 years have two children, Hilary, who is carrying on the family tradition as a teacher, and Zachary, whom Kline hopes to convert from theater student to law student.

While Kline taught he also continued his own education, earning an M. A. in American history from Lehigh University and working on a doctorate in the same subject. But before he finished the final draft of his dissertation, Kline decided to follow through on his life-long intention to be a lawyer, attending Duquesne University in 1975 - where he received the law school's Distinguished Student Award.

After he graduated from Duquesne in 1978, Kline became the last clerk to work with State Supreme Court Justice Thomas Pomeroy. He returned to Philadelphia in 1980 to work with preeminent personal injury attorney James E. Beasley. Kline credits both men with shaping his - Pomeroy with schooling him on the intellectual side of the law and Beasley with teaching him the practical side.

By 1995, Kline had already made a name for himself. At Beasley he won a $5.2 million verdict in a Dalkon shield intrauterine device suit, and another against the pharmaceutical company Merrill Dow over the nausea drug Bendectin, culminated in a $19.2 million verdict. Kline and fellow Beasley attorney Shanin Specter, son of Sen. Arlen Specter, left that firm to start their own, Kline & Specter. At Beasley, the attorneys worked in side-by-side offices and when they planned their new office space, Kline and Specter made sure to install a special pocket door between their new offices, so they could easily confer.

"I have the benefit of being involved in two partnerships, in neither of which I've had a 51 percent vote," Kline jokes. "The first one is obvious, the other is with an enormously talented partner who has built this firm with me from scratch."

Kline & Specter has grown, both in terms of payroll and practice areas. The firm now deals in class action and malpractice, in which Kline has a special passion for cases involving cancer. His mother and father both fought the disease, and Kline is currently supporting his wife in her battle against breast cancer.

Once he had his own firm, Kline's cases became a regular feature on the evening news. Among the biggest was a $51 million verdict in 1999 against the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transit Authority after a 4-year-old boy's foot was torn off in an escalator accident. In his closing arguments, Kline asked the jury for a pain and suffering award, a civil rights award, and $65 for the boy's destroyed sneakers, which the jury obliged. SEPTA was later hit with a $1million fine for tampering with maintenance evidence on its escalators and for its actions following the incident, when it blamed the victim's mother for his injury.

Since then, Kline has stayed squarely in the spotlight with other headliner cases. He has represented the families of a woman killed in the Pier 34 collapse in Philadelphia, a boilermaker who died in the Motiva Refinery explosion in Delaware, and, one of his latest, a mentally ill inmate who died at the hands of his violent cellmate at the Camden County jail.

When he's not in front of a jury winning seven and eight figure verdicts, Kline gravitates back to the classroom. In addition to his teaching from the stage, he can be found in the halls of Temple Law School and Jefferson Medical School, where he helps medical students stay out of his crosshairs.

In addition to being recognized and commended by groups and publications like the National Law Journal, Kline was asked to join the 100-member Inner Circle of Advocates - the organization of :"the nation's most celebrated trial lawyers," according to the Washington Post. He is also the regional chair of the Federal Judicial Nominating Commission, which recommends federal judges to Senators Arlen Specter and Rick Santorum.

But all of Kline's successes in law - both in the courtroom and as the number-one vote-getter in our Super Lawyers survey - may owe a debt to a certain sorry-looking hunk of metal he keeps in his cabinet. It's a reminder of the conversation with his father that set him on his course toward college and law school.

"I have this funnel that I made in seventh-grade shop class," Kline says. "When I brought it home, my dad inspected it and then turned to me and said, 'It is clear that you are going to have to learn to make your living with your head rather than your hands."